History of the Persian ceramic:

The history of the Persian pottery goes back into ancient time. Persian pottery production presents a continuous history from the beginning of Iranian history until the present day. The first earthenware was mainly of two types: black and red pottery that was decorated by geometric designs. The ancient Iranians were skillful also in designing and making pottery.

About 4,000 BC. Designing earthenware started in Iran.

Pottery had been baked more carefully in new-made kilns. Forms of these potteries indicate invention of the pottery rotating instrument may be of that time. Artists produced a variety of utensils like pots, bowls and jars to store seed. Among excavated potteries belonging to those eras, some primitive pottery sculpture of animals and birds have also been found, which had decorative value more than anything else.

The Persian pottery has a long history. Due to the special geographical position of the Iran, being at the crossroads of ancient civilizations, almost every part of Iran was, involved in pottery making.The excavations and archaeological research revealed that there were four main pottery-manufacturing areas in the Iranian land. These included the western part of the country, namely the area west of the Zagros Mountains, and the area south of the Caspian Sea – Gilan and Mazandaran.The third region is located in the northwestern part of the Iran, in Azarbaijan province. The fourth area is in the southeast, the region of Kerman and Baluchestan.

The Kavir area, where the history of pottery making can be dated back to the 8th millennium BC. The Pre-historic period of Persian pottery: One of the earliest known and excavated prehistoric sites that produced pottery is Ganj Darreh Tappeh in the Kermanshah region.

The second phase of development in pottery-making in Iran is represented by the wares that were discovered at Cheshmeh Ali, Tappeh Sialk near Kashan and at Zagheh in the Qazvin plain. The pottery of these centers is different from that of the earlier periods.

Their paste is a mixture of clay, straw and small pieces of various plants, which can be found in the desert. When mixed with water they stick well together and form a very hard paste. All these vessels were made by hand rather than on a wheel.

The pottery maker was unable to control the temperature of the kilns, and was no stable color for these potteries, it varied from grey and dark grey to black, sometimes even appearing with a greenish color. The type of pottery produced was limited, mainly bowls with concave bases and globular bodies. Their surfaces were painted mostly in red depicting geometrical patterns.

In the later periods, the wheel still had not been introduced, but the shapes of the potteries became somewhat more varied and carefully executed. The temperature in the kilns was better controlled. The decoration of the pottery now included animals and floral designs, which have been unearthed at Sialk.

To achieve a finer paste, the potters added fine sand-powder to the mixture that has already been mentioned. Thus they were able to produce earthenware with a very thin body. With the invention and the introduction of the potter’s wheel, ca. the 4th millennium BCE, it became possible to produce better quality and the number of pottery types made was greatly increased as well.

The decoration of these pottery was much care and artistic skill, and the designs used were greatly enriched and carefully selected. By that time this type of pottery was produced in several parts of Iran. Thus it reveals the close economic and cultural, that must have existed then amongst prehistoric communities.

A good example to demonstrate this connection is the pottery types that were unearthed at Tappeh Qabrestan in the Qazvin plain, which are comparable to those from Sialk and Tappeh Hessar near Damghan, all of the same period. The location of these three places forms a kind of triangle.

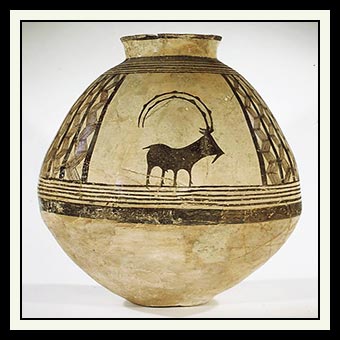

Around the 2nd millennium BCE in most parts of Iran, we have evidence of local pottery manufacture. The pottery usually consist of bowls, pitchers, jugs, and jars. Most of these wares are simple, without any surface decorations and color of these wares varies from grey to dark grey, red to buff.

Some potteries have burnished surfaces and are decorated with geometrical patterns. The most beautiful wares of that period, are the zoomorphic potteries, like humped bulls, camels, rams or human figurines, which were mainly discovered in the Gilan region (Marlik, Amlash and Kaluraz).

The zoomorphic figurines must have had two distinct functions: some of them used in everyday life, while others, probably more important, were used in religious ceremonies or in burials. Their actual function may be determined by the shape of the pottery and by the gesture of the figurines. The manufacture of these zoomorphic pottery and figurines continued until the middle of the 1st millennium BCE.

History and description of the Achaemenid pottery:

One of the most important innovations in ceramic technology appeared during the Median period was the introduction of glazed Iranian earthenware, although the earliest evidence for the use of glaze on bricks was the discovery of glazed bricks in the Elamite Temple at Chogha Zanbil, dated to the 13th century BCE.

With the coming of the Achaemenid Dynasty in the 6th century BCE great advances were made in pottery manufacture. The simple earthenware became more popular, but it was nevertheless in the finer wares that progress is most noticeable.

New shapes of pottery were introduced, like the rhyton. The surfaces were now decorated with incised and molded designs and prehistoric traditions have survived and continued. This is perhaps best observed in the application of animal figurines and sculpture.

Animal figurines are attached to the handles of jars and rhytons. These animal figurines had iconographic significance. Shapes and decorations of Achaemenid pottery disclose close connections between pottery-making and metal-working. Mostly metal shapes and decorations are produced, that one of these may add successfully in pottery.

It is during the Achaemenid period that glazing was introduced generally into Iranian plateau. Excavations at Persepolis and Susa revealed that the walls of palaces were covered with glazed bricks, which included elaborate and detailed decorations, depicting animals and soldiers. The practice of glazing must have been introduced from Mesopotamia.

Pottery of the Parthian Period: More recently in Iran a number of Parthian sites have been located and are under excavation, which are Kangavar, Shahr-e Qumis, Ecbatana and several sites in the Gorgan plain, in Gilan and Sistan. In recent studies, it has been funded that pottery was not the same throughout the Parthian Empire and the wares of Iran proper were different from Syria and Mesopotamia. Even in this area several differences are recognizable. In general, Parthian pottery can be divided into two main groups: unglazed and glazed wares.

The unglazed pottery can be further subdivided into two categories: grey and red wares. The grey pottery consists of bowls, small cups and large jars, all with convex bases and without any surface decoration. Some of them, nevertheless, have a polished body. The red ware, which was perhaps the most popular, also included large jars, bowls and jugs, similar in shape to those of the grey wares.

It also should be noted that zoomorphic earthenware, in the shape of rhytons, were still very popular in Parthian times, which were made both in grey and in red. One of the greatest achievements in pottery-making during Parthian period was the introduction of alkaline-glazed potteries.

The body of these glazed wares was a fine white paste on which the alkaline glaze could be easily applied. Two of the most common types of pottery in this group were the “pilgrim flask”, and large bowls. These types of vessels may have been produced under Far Eastern influence, since their forms recall contemporary Chinese bronzes.

The most of these Parthian glazed pottery reveal some kind of surface decoration, mostly simple incised lines or strokes. Another group of Parthian glazed pottery were the large coffins which became widely used at that period due to a change in religious beliefs concerning burial.

Pottery of the Sasanian Period: In general it could be stated that Sasanian pottery is, strictly speaking, a continuation of Parthian traditions, with two exceptions; the grey ware was practically discontinued, as were the glazed coffins, since Zoroastrian burial customs were re-introduced.

Sasanian pottery can be subdivided into two main groups: unglazed and glazed pottery. The unglazed pottery were mainly of heavily potted red clay. These include large jars, jugs, and various types of bowls, which have thick, averted rims and their surfaces now reveal intricate incised or stamped decorations, including: wavy lines, geometrical patterns, rosettes, or occasionally, even Pahlavi inscriptions.

The Sasanian red potteries have been discovered at a number of sites, such as Bishapur; Siraf, Kangavar, the Gorgan plain, Takht-e Soleyman, at Ghubayra near Kerman and Takhte- Abunasar in Fars Province.

The Parthian dark green or brownish-yellow glaze, the most important color now becomes turquoise green, or turquoise blue. This is to be found on a number of pilgrim flasks, bowls and particularly on large storage jars, which had been unearthed at Siraf and also at Ghubayra in late 1970s, in addition to glazing, were also decorated with line patterns, which run around the upper part or on the shoulder of the pottery. Terracotta figurines were also produced in Sasanian times, of which a great variety are known today.

The pottery of the Sassanian and Islamic Period:

With the advent of Islam, pottery production gradually started to change all over the Islamic world. At the beginning Iranian potters continued their pre-Islamic traditions, but due to contact with the Far East, particularly with China, on one hand and to the restrictions of orthodox Islam and considerable changes gradually took place in pottery-making, and several new types of wares were produced. Potters of the Near East made several experiments, partly imitating imported Chinese ceramics, by using their own skill and imagination in inventing new types of the pottery.

In the Islamic period, which lasted for more than a thousand years, pottery centres were established, which produced innumerable types of wares. Recent excavations in famous Islamic cities, Samarra, Siraf, Nishapur, Jorjan, etc., together with the discovery of pottery kilns at several sites, provide us with considerable information on pottery manufacture in the Islamic world. The decoration of pottery comes very close to Sassanian metalwork that was produced at Zanjan, Garrus, Amol and Sari.

It was actually a kind of Sgraffito technique, where the surface of the vessels, which always had a red earthenware body, was covered with white slip and the decorations were carved on them. The vessels then were coated with transparent green or yellow lead glaze. The decorations of pottery include floral, geometrical and frequently human and animals figures.

The Pottery of Samanid Period:

The Samanids were probably important Persian dynasties in the eastern part of the Islamic world during the early Islamic period. Their realm included large centers like Samarkand, Bukhara, Marv, Nishapur and Kerman.The most important contribution of Samanid artists to Islamic pottery-making was the invention and perfection of the slip painted pottery.

The slip-painted wares constitute a great advance in pottery decoration. The pigment runs in the kiln under the lead glaze. By the introduction of slip pigments, potters could control the designs while in the kiln, and were able to produce variety of pottery decorations.

The important group is the polychrome buff ware, decorated with human and animal figures, or rarely only with geometrical forms. Arthur Lane called this type of pottery “peasant ware” of Nishapur. This type of pottery was only produced in Nishapur, and was never imitated anywhere else in the world.

The decoration may give some indication of Samanid painting. Another group of slip-painted pottery, painted in olive-green on white or creamy ground; clearly an imitation of contemporary monochrome lustre-painted pottery. A large number of such wares, both polychrome and monochrome lustre, were excavated at Nishapur.

The second important type of Samanid pottery is that of the sgraffito wares. The simple sgraffito pottery is decorated with incised lines, right down to the red body through the thin slip which covers it, then coated with transparent yellow or green glaze. In 1976 a small fragment was discovered in the Gurgan plain.

History of the Seljuq pottery:

At the beginning of the 11th century CE, the Seljuqs came to Iran .This period under Seljuq rule in Iran lasted for more than one and a half centuries, yet it witnessed great progress in literature, philosophy, architecture and in all fields of the Iranian arts. The Seljuqs became great patrons of the arts and their patronage made it possible for Iranian artists to revive their pre-Islamic traditions and develop new techniques in metalwork and pottery.

The important achievement in pottery production was the introduction a new composite white frit material. This new white body made the application of alkaline glaze easier; the actual body of the vessels was considerably thinner, almost translucent. The potters had nearly achieved the fineness of imported Chinese Song porcelain which potters of the Near East greatly admired.

The Cities like Ray, Kashan, Jorjan, and Nishapur became the main centers of Iranian pottery production. Under Seljuq patronage the following types of wares were produced in Iranian potters: white wares, monochrome glazed wares, carved or laqabi wares, luster-painted wares, under glaze-painted wares, and over glaze-painted, so-called minai and lajvardina wares.

Another type of the pottery, which has to be added to these, is the unglazed ware, which has also gone through considerable changes and refinement. When the Seljuqs were replaced by the Khwarizmshahian Dynasty towards the second half of the 12th century, artistically the same trend continued in the Iran right up to the Mongol invasion.

Pottery of the Il-Khanid Period:

The Mongol invasions devastated large parts of Iran and in particular destroyed cities like Ray, Nishapur and Jorjan, which previously were the most important centers of Iranian pottery. Kashan destroyed by the Mongols, but have quickly recovered and pottery production continued.

Mongol of the Il-Khans, who ruled Iran on behalf of the Great Khan in Mongolia, soon separated themselves from the rest of the Empire and set up an independent dynasty. Their new capital was first at Maragheh and later at Tabriz in northwest Iran. They embraced Islam and assumed Iranian customs, culture and language. It was mainly Kashan that continued manufacturing lustre, underglaze and overglaze-painted wares. The end of the 13th and beginning of the 14th century CE, the new pottery centres emerged.

One of these was in the northwest, probably at Takht Sulayman, where the Mongol Abaqa Khan built a palace for himself, which was decorated with luster and lajvardina tiles. Takht Sulayman, however, must have been connected with another major pottery producing area, namely the Soltanabad district, which included not only the town itself, but at least another twenty or thirty villages.

Further south, Kerman became another centre and soon Mashhad pottery appears as well. Apart from these main centres there were several other, less significant, pottery producing areas, most of which haven’t yet been located. The pottery of the Il-Khanid period included: The wares of Kashan, Soltanabad and Takht Sulayman pottery, the wares of Kerman, Jorjan wares, Provincial wares.

The Timurid Pottery: Timur came with a large army, conquered the entire country and destroyed many cities, such as Jorjan, Esfahan, Shiraz and Kerman. Timur carried most of the artists away with him to his capital at Samarkand. Samarkand became the centre of the Persian arts, particularly of architecture and architectural decoration. The golden age of Timurid art, however, did not start until the reign of Shah Rukh. He was himself a calligrapher and became a patron of the Persian arts.

Persian miniature painting flourished; beautiful religious building were erected all over the Timurid realm: Architectural decoration becomes important at which time the most beautiful and elaborate faience mosaic decoration was made.

Persian pottery production of this period that the same type of pottery was produced all over, as before under the Mongols. There is more important: the first group of pottery known as “Kubachi” ware, that this ware was simply painted in black under blue or turquoise glaze, and consisted only of large dishes with averted sloping rims.

The decoration consisted mainly of floral designs or geometrical forms. There are two examples, which have inscriptions in Nastaliq and include the date of the vessels. Both give 15 th century CE dates, thus they were definitely Timurid. The name “Kubachi” in fact is the name of a small village in Daghestan.

But it was there in Kubachi, where this type of pottery was first discovered and found on the walls of houses. It is now well known that the people of Kubachi never made the pottery, but they produced fine metalwork and arms which seemed to have been exchanged for this particular type of pottery. Kubachi wares in fact was produced in the northwestern part of Iran in Tabriz.

Another type of pottery is the blue and white ware. It has already been mentioned above under Jorjan that some kind of blue and white ware was already produced in pre-Timurid times in Jorjan. The new type of blue and white, however, is different from the former in shape, color and decoration. This new type of blue and white was certainly produced under the direct influence of imported Chinese blue and white porcelain. The shapes are those of Chinese porcelain vessels.

The decoration again recalls those of Chinese prototypes, depicting lotuses, meanders and flying phoenixes. It had been suggested that this 15th century blue and white was made in Kerman. The blue and white bowls were excavated in East Africa at Kilwa, which must have been imported from Iran.

Pottery of the Safavid period:

The Safavaid dynastic period was a renaissance in the History of Iranian pottery, when Persian techniques were re-introduced and new Persian wares were invented. The rise of the Safavid dynasty as the beginning of a new epoch in the long history of Islamic pottery. The pottery of this time featured many geometric shapes, such as diamonds, triangles and stars. The Safavids came to power at the beginning of the 16th century CE, and for the first time after more than one thousand years a national and native dynasty, came to power in Iran.

The Safavid dynasty was founded by Shah Ismail, who united the country under his rule. The Safavid period was a golden age for Iranian arts and crafts. Richly decorated mosques and palaces were built: Iranian metalwork flourished again; carpet weaving gained new impetus and miniature painting reached its apogee during this time.

Shah Ismail’s successors, Shah Tahmasp and Shah Abbas the Great became active patrons of the Persian arts. First the capital was at Tabriz, and later, was transferred to Qazvin; at the end of the 16th century it was moved to Isfahan by Shah Abbas.

Iranian Pottery manufacture gained new impetus and old techniques were revived and produced. The body of these Safavid wares is now so fine, thin and translucent, that it comes very close to the imported Chinese porcelain.

It is a kind of faience but much more refined than that of the Persian potteries of Seljuq period. Safavid pottery included: Kubachi wares, Lustre wares, White or “Gombroon” wares, late blue and white wares, Monochrome and polychrome wares of Kerman

Pottery of the Zand and Qajar Periods: After the Afghan invasion of Iran when the Safavid dynasty was swept away, for a while there was chaos in the country, but pottery production must have continued along the same lines as previously.

The middle of the 19th century fine blue and white or white “Gombroon” wares were produced, but in general the quality of pottery deteriorated. With the removal of the capital from Isfahan, first to Shiraz under the Zands, and then to Tehran under the Qajar, the artists themselves moved.

The Zand architectural decoration are visible in the Majidiyeh and in other buildings in Shiraz. New colors were introduced, including pale pink. Later, tile production continued in Tehran. These tiles depict human figures in low relief against a dark blue back ground.

Isfahan produced a kind of blue and white ware and an under glaze polychrome painted ware throughout the 19th century, but the quality of these never reached that of Safavid pottery. A new type of pottery painted in blue and black with pierced decoration, again the clear glaze filling the small windows, it was made in Nayin during the 19th century.

The end of the century there was a general decline in Iranian pottery manufacture, due mainly to the mass imported and cheaply produced industrial porcelain from Europe and the china and the end of artistic pottery production in Iran.

© Fa.asadi Artwork Collection.